Vladimir Viktorovich Samsonov

(Baritone)

Distinguished Artist of Russia (2000); prize winner of

International contests (Grand-prix and People"s Choice Award at International

Opera Singers Contest of Mario del Monaco (jury: Paolo Montersolo, Lougi Alva),

Italy, 1994; Grand-prix, International TV contest ‘Engagement of Saint

Petersburg" (jury: Bulat Menzhilkiev, E.Morgunov, A.Jigarkhanyan,

L.Fedoseeva-Shukshina, I.Dmitriev), St.Petersburg – 1996, Francisco Vinas International

Contest of Opera Singers, Barcelona, 1997, Diploma; International Contest of

Opera Singers ‘Russian Bel canto Revival", St. Petersburg, 1991 – Diploma).

Born in Chisinau (Moldavia) on February 28, 1963.

Starting with describing the story about myself and

only myself would mean to totally exclude several generations of beautiful and

talented people from the process of my up-bringing – the people whom I owe everything

I know and have.

Starting with describing the story about myself and

only myself would mean to totally exclude several generations of beautiful and

talented people from the process of my up-bringing – the people whom I owe everything

I know and have.

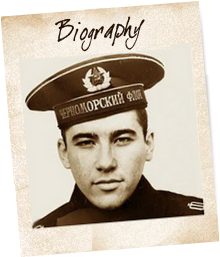

Thus, as for my ancestors, the earliest I know of is

my great-grandfather Nestor Samsonov who was a soldier of one of Petersburg"s

regiments and got wounded in the battle of Port Arthur. After the

Russo-Japanese war he was awarded imperial medals and granted a large plot of

land in Bessarabia. Subsequently, he moved there for good. The 6.5ft Russian

giant-guard got married to a miniature Maria, whose mother was Greek and father

Bulgarian named Dobrov. Maria gave birth to his ten sons, the third of whom was

my grandfather Grigory Nestorovich Samsonov. Honestly, my father remembers my

great-great-grandfather, great-grandfather Nestor"s dad, a taciturn old man,

hoary with age, leading a lonesome and rigorous life in his room. But my

father"s childish memory didn"t keep anything else about this man.

Great-grandfather Nestor was a strong and hard-working

man. Upon retiring, he planted a lot of apple-trees and vineyards in his land,

built a huge house. Several workers helped him to do the house-keeping which

included taking care of sheep, cows, horses, poultry, as well as vegetable

gardens and a deep wine cellar. Even today when you cross the Dniester River on

the bridge from the side of Bender town to Tiraspol, you can see a no-man"s

land in which a vast apple orchard used to whiteblossom.

Then the revolution came, and my great-grandfather got

into Chisinau prison for he secretly helped the Bolsheviks to transport weapons

to the other bank of the Dniester. By chance he shared the prison cell with the

famous Kotovsky who highly appraised great-grandfather"s heavy fists and

offered him to escape together. Nestor refused, and the same night Kotovsky

escaped. Having sowed the window bars, wrapped his legs with blankets, he

jumped out of the window on the third floor of the prison. When the Bolsheviks

seized the power, they considered great-grandfather a kulak and expropriated

everything that was deemed “acquired unjustly” including sheep, horses, cows…

and the apple-tree orchard. My great-grandfather lived a long life, reached the

end of the 1970s and died quietly just a little bit under the age of 90.

But the true matriarch of the large Samsonov family

was a miniature great-grandmother Maria. She lived until 94 and to the very end

remained the true centre of the family and our supreme leader. All her seven

sons never questioned her word and truly loved their dear mother. Even I was a

witness of splendid celebrations in the

parents" main house in Parkany village where all the brothers gathered with

their wives, children and grandchildren. Home-made Moldavian wine flowed freely

as well as songs accompanied by after-war trophy accordions.

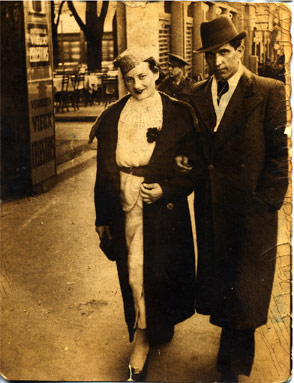

After the Civil War and signing of the Brest Peace Treaty

by Lenin, the part of Bessarabia where by natives lived was surrendered to the

kingdom of Romania. My grandfather, Grigory Nestorovich, a very young man at

that time, went to Bucharest to get a trendy profession of an artist

photographer. There he met and then married Stepanida Vasilyevna Vranchan, my

grandmother. Her ancestors were Romanian nobles. Her father, my other

great-grandfather, Vasily Vranchan, was a village priest. He was a highly

educated and intelligent man. As for her wife Eudokia from Ukrain, in other

words, my great-grandmother Dusia, I remember her myself and very clearly. As

well as the above-mentioned great-grandfather Nestor and great-grandmother

Maria. It is thanks to the Vranchan family that most of us inherited opera

voices. Thus, my father"s aunt by mother was an opera diva first in Bucharest

opera and then in Chisinau. The uncle of my grandmother Stepanida was a famous

bas soloist of Mariinsky Emperor"s Opera House and singed there with Shalyapin

himself.

After the Civil War and signing of the Brest Peace Treaty

by Lenin, the part of Bessarabia where by natives lived was surrendered to the

kingdom of Romania. My grandfather, Grigory Nestorovich, a very young man at

that time, went to Bucharest to get a trendy profession of an artist

photographer. There he met and then married Stepanida Vasilyevna Vranchan, my

grandmother. Her ancestors were Romanian nobles. Her father, my other

great-grandfather, Vasily Vranchan, was a village priest. He was a highly

educated and intelligent man. As for her wife Eudokia from Ukrain, in other

words, my great-grandmother Dusia, I remember her myself and very clearly. As

well as the above-mentioned great-grandfather Nestor and great-grandmother

Maria. It is thanks to the Vranchan family that most of us inherited opera

voices. Thus, my father"s aunt by mother was an opera diva first in Bucharest

opera and then in Chisinau. The uncle of my grandmother Stepanida was a famous

bas soloist of Mariinsky Emperor"s Opera House and singed there with Shalyapin

himself.

His voice was phenomenal by power. My father remembers

when in the middle of some celebration the guests asked uncle to “show his

trick”, and after a long persuasion he took a kerosene light, sang a low tone

and extinguished the fire without even removing glass cover. Later, when I

lived in St. Petersburg, I found his name and address - Drovyanoy lane - in the

old phone book dated 1913.

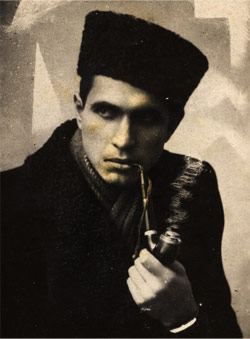

Soon after, my grandfather Grigory opened his

photographic studio in Bucharest. My father Victor who was born in Bucharest on

June 27, 1937 told me about a big house of his parents, servants, and a large

case with money kept under a bed (my grandfather"s business was very popular at

that time, so he flourished).

The idyll ended in 1939 after signing of a well-known

pact between Molotov and Ribbentrop. Vast territories of Romania were

surrendered to the USSR, and there, in Lepkany village, the main value of my

family remained - the parents. My grandfather left everything in his dear

Bucharest, moved to Bendery with his family to stay with his parents. At that

time everybody knew perfectly what Stalin"s “iron curtain” was and understood

that they may have parted forever. And my father had to hide from the KGB"s

vigilant eye the fact of his birth in a capitalistic country.

In Bendery, grandfather Grigory became director of a new

Soviet photographic studio No. 1 and received state salary for his service. He

took pictures of visitors for documents, made portraits of foremost laborers

for Honorable Boards, made some additional earning on weddings and burials. By

the way, I clearly remember how he instructed me when presenting my first photo

camera FED-3 for my thirteenth birthday: “Remember, boy, the most responsible

shooting is at the burial. If you screw up with the film, nobody will dig the

deceased out to make another shot”.

In Bendery, grandfather Grigory became director of a new

Soviet photographic studio No. 1 and received state salary for his service. He

took pictures of visitors for documents, made portraits of foremost laborers

for Honorable Boards, made some additional earning on weddings and burials. By

the way, I clearly remember how he instructed me when presenting my first photo

camera FED-3 for my thirteenth birthday: “Remember, boy, the most responsible

shooting is at the burial. If you screw up with the film, nobody will dig the

deceased out to make another shot”.

And then came 1941. The war. My grandfather was

recruited to the Red Army, and assigned with command of a platoon of

construction battalion. He was sent on mission with a platoon of Moldavian

peasants who didn"t even talk Russian to build fortifications near Sevastopol.

Father remained with his mother, my grandmother Stepanida, in Bendery. He

remembers as one day unknown airplanes flew high in the sky and in one day

Soviet soldiers abandoned the town without fight. And the next day the Germans

entered the city. The big family of Samsonov hid in the wine cellar disguised

under a haystack. The Germans settled themselves in the abandoned house without

any idea that a whole family was hiding just near, in the yard.

And then came 1941. The war. My grandfather was

recruited to the Red Army, and assigned with command of a platoon of

construction battalion. He was sent on mission with a platoon of Moldavian

peasants who didn"t even talk Russian to build fortifications near Sevastopol.

Father remained with his mother, my grandmother Stepanida, in Bendery. He

remembers as one day unknown airplanes flew high in the sky and in one day

Soviet soldiers abandoned the town without fight. And the next day the Germans

entered the city. The big family of Samsonov hid in the wine cellar disguised

under a haystack. The Germans settled themselves in the abandoned house without

any idea that a whole family was hiding just near, in the yard.

Grandfather told me that at the same time the Germans

blocked access to Sevastopol from land, connection with his platoon was broken,

and they remained in the fortified area alone, with spades and pick hammers

only. Nobody ordered to abandon the post, so he remained there with his platoon

waiting for orders. In the evening an infantry battalion came from the

frontline. The battalion commander offered them to join and leave for

Sevastopol. Up in the morning, grandfather saw that the battalion left and

everybody just forgot about them. Then the situation was evolving quickly.

Something roared and rose dust clouds over the eared ploughland where the

platoon was digging entrenchment. It was obvious that a German motorized

infantry was approaching. Grandfather made his last order to his fellow

countrymen in Moldavian: “Disperse and move to ally forces". Everybody

dropped the tools and rushed to the forest. Grandfather ran to the neighbouring

village. In the first house on the way where grandfather passed an old man

lived with his daughter. In that house he changed his uniform for civilian

clothing. Hardly had they hidden the Soviet officer"s uniform, as the Germans

slammed into the house. Having torn away grandfather"s cap they shouted

"Russisch soldaten?” As grandfather understood later, they identified

Russian soldiers by clean-shaven heads, and since grandfather was an officer he

had a haircut though short. The Germans went to the other houses, and

grandfather waited until the evening, took some food and left for the forest.

Then an incredible story began. Grandfather went on foot the distance from

Sevastopol to Bendery. Over 2000 kilometers. He started his walk in summer and

arrived there in winter. He was moving at night in order not to be captured by the

Germans. Without documents, feeding himself with berries and mushrooms only, he

reached Sivash. There he joined some other refugees passing by enemy

roadblocks. Hungry they were, and in the basement of an abandoned house they

found some potatoes but could not eat them. Those who were unable to take them

along, poured the potatoes with gasoline.

Grandfather ran to the neighbouring

village. In the first house on the way where grandfather passed an old man

lived with his daughter. In that house he changed his uniform for civilian

clothing. Hardly had they hidden the Soviet officer"s uniform, as the Germans

slammed into the house. Having torn away grandfather"s cap they shouted

"Russisch soldaten?” As grandfather understood later, they identified

Russian soldiers by clean-shaven heads, and since grandfather was an officer he

had a haircut though short. The Germans went to the other houses, and

grandfather waited until the evening, took some food and left for the forest.

Then an incredible story began. Grandfather went on foot the distance from

Sevastopol to Bendery. Over 2000 kilometers. He started his walk in summer and

arrived there in winter. He was moving at night in order not to be captured by the

Germans. Without documents, feeding himself with berries and mushrooms only, he

reached Sivash. There he joined some other refugees passing by enemy

roadblocks. Hungry they were, and in the basement of an abandoned house they

found some potatoes but could not eat them. Those who were unable to take them

along, poured the potatoes with gasoline.

When they reached the Dnieper in the late fall,

grandfather had to cross over the bridge where he was detained for he had no ID

on him, and sent to the German commanding office. There he also got some luck.

A Russian woman who issued documents made him an “Ausweiss”. When grandfather

reached the basement in native Bendery, his legs grew numb due to many nights

spent in wet forests. Later on grandfather managed to resume walking. I

remember us going to Odessa estuaries to get some mud treatment for

grandfather"s legs.

Four years passed, and the Victory Day came. The Germans

were forced out of Bendery and still did not know that a whole family lived in

the same yard with them, while men went out secretly in the night to fetch some

water and food.

Four years passed, and the Victory Day came. The Germans

were forced out of Bendery and still did not know that a whole family lived in

the same yard with them, while men went out secretly in the night to fetch some

water and food.

Then the hungry 1949 came when people, as father

remembers it, died in the streets. Our family survived because grandmother

Stepanida, as if she foresaw such a nightmare, made a lot of canned chicken.

Grandfather Grigory was a true businessman at heart

and an advocate of capitalism and private property. He worked hard and

successfully. He respected only those people who were masters of their matter

and could make good money. In the 1950s he went to work in Naryan-Mar. After a warm

Moldavia, my father remembered severe frosts and a semiannual polar night for

the whole life.

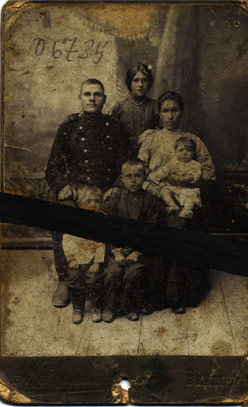

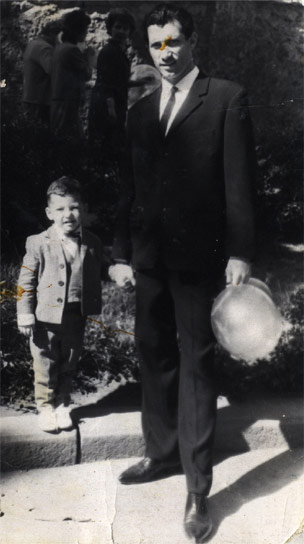

In 1956 my father Victor was called to serve the Army.

He finished the driving school at the training grounds and assigned to the tank

regiment as the driver of lorry with canon and its crew. Almost immediately

after their arrival to the disposition, they were boarded onto the railway car,

and on the following morning the 19-year old boy found himself in the crucible

of mutinous Hungary. I remember his story about one day when the Russians were

first ordered not to shoot and resist provocation. Hungarians, being sure in

their impunity, surrounded his car and started to hit it with sticks and throw

stones. Words and persuasion enraged the crowd even more. My father was lucky

that an ally GDR patrol came nearby. Having quit the car and immediately

understood the situation, the German officer drew a circle around the father"s

car and calmly promised the Hungarians to shoot anyone who crosses the line.

The memory of German punctuality was so vivid at that after-war time that

nobody approached the father"s car anymore.

Father"s military service lasted over three years and

ended in Kazakhstan where he was engaged in land development. Father

transported grain. He saw a lot in those wild lands where the Soviet law had no

power, and the rules of criminal gangs were in force. There Chechen people

banished as enemies of the state lived in accordance with their own laws, and

those who did not want to obey such laws would not live a long life. There were

no roads, and people who lost their path in the blizzard of virgin land burnt

their cars just not to freeze to death.

Father"s military service lasted over three years and

ended in Kazakhstan where he was engaged in land development. Father

transported grain. He saw a lot in those wild lands where the Soviet law had no

power, and the rules of criminal gangs were in force. There Chechen people

banished as enemies of the state lived in accordance with their own laws, and

those who did not want to obey such laws would not live a long life. There were

no roads, and people who lost their path in the blizzard of virgin land burnt

their cars just not to freeze to death.

Having returned to Bendery, the father as well as all

men of the Samsonov family did not remain in the native town but went to take

chances in a new place - Chisinau, a capital of Moldavia.

By that time he already started signing in Bendery

town choir of amateurish performance, and its leader convinced my father"s

parents that their son would have a great artistic future. But father had to

earn his living, and he got employed as a driver of ambulance car in Chisinau

republican hospital. At the same time he entered Chisinau music school to the

signing department.

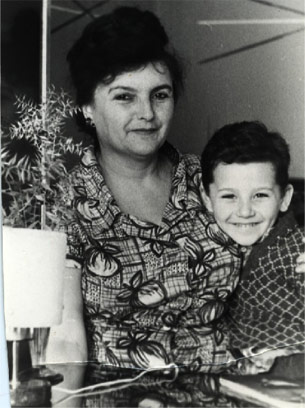

Here the story of my family comes close to me

personally, since in the same hospital No. 4 where my father drove doctors on

emergency visits, there worked one girl with splendid black hair and

almond-shaped tea-coloured eyes – my future mother Zoya.

My mother together with her elder sister Tatyana was

brought up in a small room in the street of Stephan the Great by my grandmother

Frida, a widow of a Red Army officer missed in action during WWII. In 1941 she

remained alone with two daughters, and during her whole life she was proud that

she managed to bring up and give higher education to both of them.

Grandmother Frida was born in Latvia. The elder

daughter of a shoemaker in Riga, she grew up in a family with many children,

and early in the childhood she learnt what hard toil was. Contrary to

successful capitalistic family of my father, she was brought up in the best

traditions of Soviet “anti-parasitic communist” ideology. She became one of the

first pioneers. She went to surplus-appropriation campaigns where she took away

grain hidden by rich peasants and brought it to starving labourers, sincerely

believing that it was the right thing. Then she worked (like a mule, as she put

it) all days long at a stamping machine pulling steel sheets to the press. She

sang “the Internationale” and was a cheerful Soviet enthusiast who firmly

believed that all hardships should be overcome sternly, and bright communistic

future was ahead of us. I will never know how she got acquainted with my smart

grandfather Vladimir, a Red Army officer, in whose honor I was named. I know

only that they loved each other passionately, and no troubles could ever break

their feelings. And the 1930s were troublesome for everybody, my grandfather

being not an exception. When after the unveiling of “conspiracy” of marshal Tukhachevsky

there became a “cleansing” in the commanding ranks of the Red Army, my

grandfather Vladimir being an artillery officer, was investigated by the NKVD.

Grandmother Frida was born in Latvia. The elder

daughter of a shoemaker in Riga, she grew up in a family with many children,

and early in the childhood she learnt what hard toil was. Contrary to

successful capitalistic family of my father, she was brought up in the best

traditions of Soviet “anti-parasitic communist” ideology. She became one of the

first pioneers. She went to surplus-appropriation campaigns where she took away

grain hidden by rich peasants and brought it to starving labourers, sincerely

believing that it was the right thing. Then she worked (like a mule, as she put

it) all days long at a stamping machine pulling steel sheets to the press. She

sang “the Internationale” and was a cheerful Soviet enthusiast who firmly

believed that all hardships should be overcome sternly, and bright communistic

future was ahead of us. I will never know how she got acquainted with my smart

grandfather Vladimir, a Red Army officer, in whose honor I was named. I know

only that they loved each other passionately, and no troubles could ever break

their feelings. And the 1930s were troublesome for everybody, my grandfather

being not an exception. When after the unveiling of “conspiracy” of marshal Tukhachevsky

there became a “cleansing” in the commanding ranks of the Red Army, my

grandfather Vladimir being an artillery officer, was investigated by the NKVD.

After a false denunciation he was expelled from the

party, and then arrested. Only strong support and a brave defense of the

commander of his regiment saved my grandfather and my mother"s family from an imminent

death. Grandfather got party membership and military rank restored. Soon

grandfather"s division was moved to Stavropol where my mother was born. The

commander wished with all his heart to have a son, but the second daughter was

born. Grandmother told that grandfather was so upset that did not even want to

look at the child. But after he saw a pretty angel he devoted all his life to

his “little Zoya”.

It seemed that after the NKVD nightmare the bad story

was over but dark clouds came from another side. In winter 1941 grandfather"s

division was moved to the western border. All officers were ordered to leave

their families in Stavropol. From that time, only a few grandfather"s letters

survived where he told my grandmother not to worry because everything would be

fine, “Stalin is a great leader, and the victory will be ours”.

In June 1941 his division was the first to meet a ruthless

German war machine on the border. All his heroic division did not make a step

backward and was massacred leaving almost no survivors. Some of those who

survived this told grandmother that saw my heavy wounded grandfather in

hospital at the moment of emergency evacuation – the Germans already pushed

through to the suburbs of the town where the military hospital was located.

Nobody was trying to rescue the heavy wounded, and grandfather was left to his

fate. We can only guess what a torturous death he saw. The Germans showed no

mercy to heavy wounded. Thus, my grandfather Vladimir became “lost in action”.

It seems strange but the files of the division remain confidential, and even in

the archive on Mount Poklonnaya my mother"s request to know the fate of

grandfather was rejected.

Grandmother Frida was my guardian angel in all senses.

If anyone loved me so whole-heartedly, devotedly, to distraction and without

question, that was she – my grandmother

Frida. She considered me, her dear Vovochka, a genius, and did not even try to

keep it to herself. I remember her running after me and breathing heavily when

I was learning to run on rollers, or running after my bicycle and holding the

rear rack when I swayed trying to keep balance. She played badminton with me,

hitting with the racquet as if with a sword. And what kind of respect I earned

from my fellows when we paused the game and ran under grandmother"s balcony,

and she answered my call, pulling down a flask with water on a rope from the

fourth floor. I remember her amber-coloured transparent jam from white cherries

with almond nuts, and the chops so delicious that it seemed you could never

have enough of them… She lived up to 83 years old, she saw my wedding, played

with her grandson, rejoiced at my victories at opera contests and debut

performances in Mariinsky Theatre and Grand Opera House. She lied in coma for thirteen

days and died only when I arrived, at the very moment when I entered my

parents" apartment where she lived together with them. Now her remains rest at

Chisinau cemetery, and the gravestone has the pictures of herself and my

grandfather Vladimir, a Red Army officer who lies not in the same grave yet

remain in her heart throughout the whole life.

Grandmother Frida was my guardian angel in all senses.

If anyone loved me so whole-heartedly, devotedly, to distraction and without

question, that was she – my grandmother

Frida. She considered me, her dear Vovochka, a genius, and did not even try to

keep it to herself. I remember her running after me and breathing heavily when

I was learning to run on rollers, or running after my bicycle and holding the

rear rack when I swayed trying to keep balance. She played badminton with me,

hitting with the racquet as if with a sword. And what kind of respect I earned

from my fellows when we paused the game and ran under grandmother"s balcony,

and she answered my call, pulling down a flask with water on a rope from the

fourth floor. I remember her amber-coloured transparent jam from white cherries

with almond nuts, and the chops so delicious that it seemed you could never

have enough of them… She lived up to 83 years old, she saw my wedding, played

with her grandson, rejoiced at my victories at opera contests and debut

performances in Mariinsky Theatre and Grand Opera House. She lied in coma for thirteen

days and died only when I arrived, at the very moment when I entered my

parents" apartment where she lived together with them. Now her remains rest at

Chisinau cemetery, and the gravestone has the pictures of herself and my

grandfather Vladimir, a Red Army officer who lies not in the same grave yet

remain in her heart throughout the whole life.

I think that my today"s lucky fortune has direct

connection to the day when my parents met – April 12, 1961. On that day the first

man flew into space!

The last winter day of 1963, February 28, became my

birthday. My mother was a true hero. Giving birth was absolutely

contraindicated to her, since one of her kidneys was misplaced. And the process

was not easy – I was a robust child, and she was such a miniature woman (her

father could take her waist in the ring of his fingers), so the best obstetrics

professor in Chisinau pulled me with forceps.

By that time mother finished her studies in the

technical school, and when I was 7 she graduated cum laude from the Economic

Department of Chisinau Technical University.

At that time we lived in Chisinau, in Andreevskaya

street, 19. That one-storey old house, the first thing I remember in my life,

was destroyed during an earthquake in Chisinau in 1977.

But that was much later, and in autumn 1970 I went to a

specialized English language school No. 2. Yet I studied there for three years

only. By that time father who sang in “Doina” choir and Chisinau Opera House,

brought my mother and me to Sevastopol where he served and sang in the Ensemble

of Song and Dance of Red Flag Black Sea Fleet. Boris Bogolepov, the legendary

leader and founder of that ensemble, was charmed with appearance and voice of

my father. I met spring 1973 in a small but cosy apartment near the Black Sea,

a hundred meters away from the diggings of the ancient Greek town Chersonese,

in the street with a wonderful name – the Ancient Street. Getting ahead, I want

to say that Boris Bogolepov, a musician with amazing talent, played a

considerable role in my life, too.

But that was much later, and in autumn 1970 I went to a

specialized English language school No. 2. Yet I studied there for three years

only. By that time father who sang in “Doina” choir and Chisinau Opera House,

brought my mother and me to Sevastopol where he served and sang in the Ensemble

of Song and Dance of Red Flag Black Sea Fleet. Boris Bogolepov, the legendary

leader and founder of that ensemble, was charmed with appearance and voice of

my father. I met spring 1973 in a small but cosy apartment near the Black Sea,

a hundred meters away from the diggings of the ancient Greek town Chersonese,

in the street with a wonderful name – the Ancient Street. Getting ahead, I want

to say that Boris Bogolepov, a musician with amazing talent, played a

considerable role in my life, too.

At that time my father dreamt that his son would

become something that he was unable to be himself – a military pilot. Since my

childhood I was surrounded with his dream about the sky. Photos and models of

airplanes were everywhere in our house. Father prepared me for the military

school, so he made me go in for boxing, and later upon his suggestion I spent six

years going in for pistol shooting.

It is remarkable that I won my first boxing match at

the age of twelve when my father was my second in the corner of the ring. He

was a champion of the division in box and a candidate master of sports in

pistol shooting, so he always advocated development of my personality in

sports. I remember well when I was sixteen, and my father took me to Mount

Vishnyovaya where together with other crazy amateurs of sky we trained to fly

on self-made delta planes.

When I was fifteen, I finished by eighth year of study

at school, and my parents decided that I should enter Sevastopol Technical

School of Sea Vessel Construction. I did not have any notion what I would like

to be, though I could make decent drawings since I studied in the school of

fine arts, and I sang in the school amateur performance club, and won first

prizes in the town and even at children festivals of the country. Generally

speaking, I did not care about anything but whether my parents would let me go

with my fellows to sea, so I entered the school as my mother told me, and I put

my best effort into trying to learn something from it. However, my purely

humanitarian thinking refused to learn such horrible things as theory of

strength of materials, theory of mechanisms, perspective geometry, higher mathematics and electronics. I still

remember such a terrifying subject as Electrical Systems of Sea Vessels. I took

examinations in it eight times. But soon my studies became easier, not because

I got much smarter, but because I became the chief editor, artist, and

photographer of the school newspaper, and later, which is the most important,

the leader and main voice of our rock band. But this period of my life when it

drastically changed and gained pace will be described in the “History of

projects” section.

So, teachers got softer on me for my achievements in

art, and in 1982 I successfully defended my graduation paper.

I remember bringing home my new blue credential

smelling with fresh publishing paint, and I told my mother: “Take it since I

will never need it”. To some extent I was right. I submitted it as the

educational certificate upon entering Leningrad Conservatory, and I never saw

it again. The HR Department of the Conservatory lost my diploma of the

Technical School and thus forever closed the door to the world of frames and

vessel generators. Ahead laid a beautiful but extremely difficult and endless

way to Music, which was the essence of my life and dreams.

And here I came to the part of my biography where my

life way started to fork in two and sometimes even more paths, all of which

were extremely interesting to me, and which I would hate to miss, and along

which I ran simultaneously in an attempt to learn and try everything in such a

wonderful WORLD OF MUSIC.

Read about each of these paths in such sections as “Works”,

“Opera”, “Operetta and musicals”, and “Projects”.